The FAA Is Further Behind in UAS Regulation Formulation but Is Open to Solutions…Sort Of

Discussing Remote ID, UTM, BVLOS Operations and Complex Waivers

The FAA has long struggled with catching up to new technologies. In the past, the federal agency has had more time to make decisions on rolling out regulations due to the pace of technology. Now, the pace of technology is so fast, the FAA is struggling to keep up. And the data actually shows us that we are further behind than we ever expected.

This past week I attended the FAA UAS Symposium 2018, the FAA’s conference to discuss the direction of the industry and help pilots understand the current state of the drone world. This conference showed us that while the FAA is really struggling to keep up with the technology as it grows…it is clear that the attitude of the agency has changed dramatically. But it has changed for the betterment of the industry. In the past, prior administrations would essentially give the impression of “let us figure it out, we got this.” This conference had a very different tone, the FAA really branded the concept that they’re willing to listen to the UAS community and want feedback from market players to advance the drone market as we know it today.

The only problem with the “we’re listening,” rhetoric is that the FAA could potentially be listening to the wrong audience. The FAA has prioritized the words and recommendations of the much larger companies rather than the small businesses. The small businesses that actually operate in the national airspace system, the guys who are owners and pilots. They’re not lawyers and strategists. In essence, the FAA’s decision to hear out the big whales makes sense as these larger companies have interests to develop systems that can vastly grow and scale their drone business in the market as we know it. They’ll save millions of dollars, create new jobs and increase efficiency. These aerial systems will also take significant infrastructure, example BNSF railroad creating control stations along their railroads for takeoffs and landings of fixed wing, BVLOS aircraft. (BVLOS: beyond visual line of sight).

Albeit the argument makes sense, it is necessary to beg the question, “Why not listen to the small business operators?”. Why not listen to operators that have real world experience in the field? The little guys represent about 95% of the 75,000 licensed drone pilots in the United States. The major players have the time and money to be patient and figure out how to implement autonomous, often times, long range operations with drones.

The big players can spend time and money to have an ear with the FAA, they have spent significant money just to have lobbyists pound pavement in Washington, albeit with little success.

(CNN took 2 years to acquire a “flight over people exemption,” spending hundreds of thousands of dollars to a max height of 21 feet and are required to use a tethered drone) wow……

Since 2016, when Part 107 was implemented, these large businesses have been hustling to waive certain sections of the law. If they can acquire an exemption from the FAA to operate beyond visual line site, or fly over people for news… then they can solve significant problems and offer new solutions to their clients & customers.

The only issue is that these large companies have time and money, what about the startups that would like to solve problems for other companies that are often unwilling to explore new solutions? Well, the FAA has successfully setup an environment where startups are often started with a pathway to failure if their operations fall into a waiverable category. They’ll be waiting years to complete simple operations that take place in other countries, all over the world, everyday. At what point is the FAA breaking its Congressional requirement to provide a pathway for integration of drones in the NAS?

Major Themes:

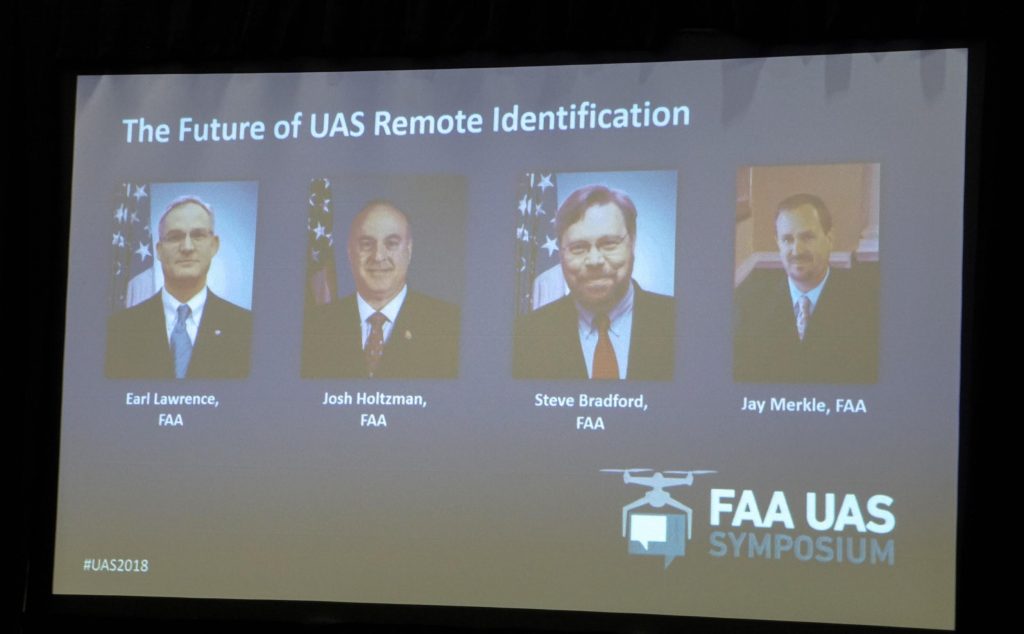

This conference covered a few major themes which would have a significant impact on the industry as a whole. One major theme is pushing Remote Identification on all UAS. Remote identification would be a requirement to all future operations. Remote ID would be used to broadcast a drone’s position so other aircraft and law enforcement have an idea of who’s flying what and where.

The FAA believes that Remote ID would provide a few simple solutions which could then multiply other solutions on the FAA’s end, and allow for more operations. Remote ID could be the system that allows for further growth in drone integration, and the safety of the National Airspace. In the eyes of the FAA, remote ID would allow for law enforcement to identify drones and their operators. In addition, it would allow all aircraft to view each other’s position in the NAS. It would also provide a way for remote pilots to always know the location of their vehicle, in the unlikely event of an accident.

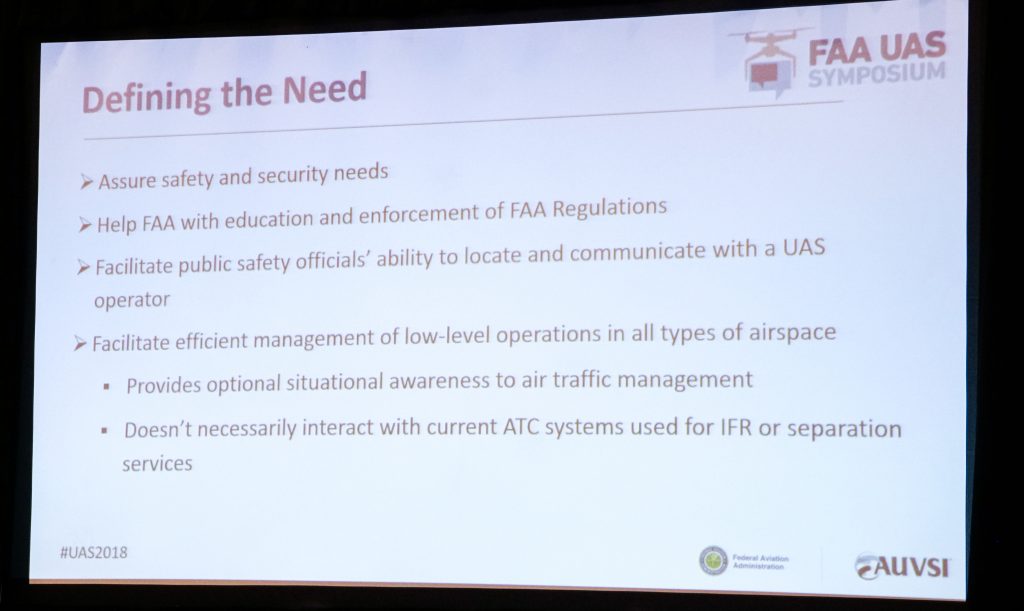

Remote ID would also become the first system to be implemented to advance the new UTM, or universal traffic management system that could be the quintessential key allow these larger autonomous operations of drones. Think amazon delivering packages, flying railroads for inspections, and mapping roads for autonomous cars. The FAA called UTM the “system of systems” to allow for autonomous operations, BVLOS operations, flight over people operations, and other unique operations that help businesses acquire data and solve problems.

During the 2018 FAA symposium, the FAA discussed the real need for Remote Identification or Remote ID on drones

Earl Lawrence did an astounding job of being open to solutions for remote ID. He and the other FAA officials made it abundantly clear that they wish to find a solution to remote ID in a cheap and efficient way, that wouldn’t add additional weight to existing drone systems. In addition to this pro-business mindset, the FAA stated that the only solution to this system would have to be a performance based standard. With performance based standards, if the technology accelerates, the system scales with it. That is commendable. Many of the whales (larger drone companies) offered systems and potentially theories of how remote ID could be implemented. Project Wing, a subsidiary of Google, offered a 5 step solution that would seem pretty simple. DJI, the world’s largest manufacturer of drones has a solution of its own. Currently, a majority of the systems they sell today could actually broadcast remote ID and even turn the data into a “TCASS like,” system. The current aircraft offered by DJI have the computing power to even communicate with one another. Does that mean DJI could flip a switch and boom problem solved?

For those aviators out there who aren’t familiar with TCASS, this system communicates position information to other planes and helicopters. This system also tells southwest airlines if another plane is on the same trajectory and the flight controller will automatically adjust its path to avoid collision. If DJI’s existing systems can already promote Remote ID, why not use them? It’s easy to believe that pilots are weary of their privacy and who sees the data. The FAA even said, on multiple occasions that they are getting into the data business. So who owns the data and who will have access to it? Many people are afraid remote ID would infringe on privacy, while others see it as a pathway to complex operations, as we can “see” who’s flying and where.

Drones have to be integrated into the national airspace system in a manner that allows for scalability for autonomous operations

Do you notice if common theme here? Businesses are investing millions of dollars to figure out what the government should have already figured out, but the fact that the FAA is proposing these regulations and asking for feedback is outstanding. . Think about it, DJI released a Remote ID system late last year in Washington D.C. They also displayed a system (Aeroscope) for law enforcement to view the remote ID of any drone. This expensive system works well in determining rogue drones from authorized flights. Although any tech savvy millennial would tell you to spend $150 on a large wifi antenna and kismet to acquire the same data….

Many industry leaders I spoke with believe that remote id is the key to widespread access to exemptions and new opportunities.

Waivers and Exemptions (aka the same thing and the true gateway to expand operations)

In the eyes of the FAA, Remote ID could open the door to the system of granting waivers more easily and efficiently. Therefore allowing for many more operations that would require specific regulations to be waived. Under part 107, drone operators have to stay line of sight, below 400 feet and cannot be flown over people. While there are more regulations than just that, I’m limiting the discussion to those for the sake of keeping this article short. The information below detail just how many people have applied for specific regulations to be waived, and how many individuals have been successful in obtaining these waivers or exemptions. These exemptions would allow pilots to offer more services, and more easily scale those services.

Looking at the rates of approval versus denial is pathetic. The number of BVLOS exemptions is 14. Why is that a problem? Drones are good at doing a few things, flying low and slow. We can get better detail, better photos, information and accuracy from the sky than traditional helicopters, at a cheaper rate. This means we can canvas property, and create topographical maps, orthomosaics, and point clouds that offer unprecedented data.

Even Intel showed off their photogrammetry and 3D modeling services, and honestly it can be done much faster than what they displayed. (Only something you would know if you’ve flown hundreds of mapping missions) This data has many different uses from the US geological survey, to ensuring you actually own the property you say you own when selling a house!

Under Part 107 regulations, drones can only fly “line of sight.” Which if you have perfect vision, you’re not going to fly more than 2,250 feet away from yourself. Under most operations, that is plenty of space to fly for shooting real estate, mapping golf courses (barely), or filming small productions for corporations and feature films. The problem is that in order to scale these operations, a drone operator needs to be able to fly significantly further than VLOS in order to compete with helicopters. There are dozens of federal contracts asking for photogrammetry and aerial photography services, but are truly inoperable for drones. This is directly attributable to the need to stay within VLOS. It also takes way too many personnel to fly the mission with a drone. If I wanted to map the entire coastline of Florida with a drone in order to more accurately measure erosion, it would take much too long since each flight is limited to 2250’ in any direction. Why not just fly a helicopter? Right now there may not be another option, even though helicopters offer a decreased level of data and accuracy. If a drone pilot can fly that mission BVLOS, it would be safer and the data could be more accurate. But current BVLOS restrictions prevent this. The technology is there, but the regulations needlessly prevent the operation.

As mentioned at the conference this week, BNSF is part of the pathfinder program of the FAA, testing their BVLOS operations in an attempt to gather data on the operations, and gain insights into BVLOS successes and failures. Obviously the FAA had to start somewhere to acquire data to make data-based-decisions on BVLOS operations, but it may be plausible they are not exploring other avenues in order to acquire data and make better decisions.

BNSF railroad explained this week that pilots who fly these BVLOS drones have a fixed wing pilot instrument rating: A certificate that takes about $10k in order to acquire a pilot’s license. It also requires hours of work, additional financial resources, training and testing in order to acquire an instrument rating. For those of you who are not familiar with the differences between Part 61 pilots (fixed wing, Cessna pilots) and Part 107 pilots, it is a difference of about $9,850 in price. Part 107 (Drone Pilots) can take a test, pay the feds $150 and start flying drones for money.

For the FAA to impose an instrument rating requirement so operators can fly a drone BVLOS seems absurd. It’s a archaic approach to an quickly evolving technology. It is easy to understand the train of thought, pilots will be flying fixed wing drones long distances and need to understand how to fly off of their telemetry data only. Why not require telemetry based training on drones to do the same thing? Without this data, how would we know how the average drone pilot can handle these operations? How would we know a pass/fail rate of a regular drone pilot taking advanced training to operate in BVLOS operations?

In order to scale this industry and allow companies to truly take advantage of these flying platforms (a reference from my book Livin’ the Drone Life) we need companies to be able to quickly acquire exemptions in order to fly beyond visual line of sight. We need companies to have a system to acquire exemptions to fly over people.

While the FAA plans to unveil the system to acquire a flight over people waiver in early May, it will require significant equipment costs, i.e. a ballistic parachute system.

Without a streamline system to make decisions based on performance and safety, pilots are struggling and the FAA isn’t moving fast enough. Is it fair the administration could be afraid of making a mistake and have blood on their hands? Simply put, the FAA is operating from a negative leveraged position. They are more afraid of failing and the risk involved therein, than providing a way to capture more data and make decisions more intelligently to move forward.

This argument is made with the understanding that there are roughly over 8 million drones buzzing the skies of the United States. Of which, there have been one confirmed crash with a helicopter, and zero confirmed crashes with planes. All the while, manned aircraft has dozens of crashes and accidents on a daily basis. Drones are inherently safe, but the risk mitigation policy of the FAA is leaning too far towards indecisiveness for them to effectively acquire data in order to make decisions and advance the market as a whole.

Hobby Pilots & 336 may be about to end

During one of our recent episodes of Ask Drone U, we detailed the findings from our FOIA request on enforcements against illegal drone pilots. The FAA is absolutely taking a compliance standard of enforcement which emerged from the days of FAA agents harassing would be pilots. But this stance may actually hurt the UAV industry, and the ability for rulemaking with credibility.

I believe the FAA has devised a plan to squelch most rogue operations that occur with hobbyists . Defining problematic hobbyists: We’re talking about someone who gets a drone and becomes a photographer or videographer. He goes to Best Buy or Amazon, buys a drone, and flies it in restricted airspace to get photos, and caused harm to a helicopter. (Case in point, last year’s Phantom vs. Blackhawk incident).

There were many inferences that Congress may be revisiting section 336, which provides hobbyists the rights to fly free of major rules. It seems they may have something up their sleeve. This will cause the lobbying arm of the AMA go into full force. While I believe more enforcements are needed, it probably won’t occur until the new rules are unveiled. Section 336 of the FMRA of 2012 may have had good intentions, but it basically ended up tying the hands of the FAA. Changes to the 336 regulations with stricter rules to hobbyists could potentially benefit commercial drone operators. Especially if the FAA provides a better means of enforcement for LEO’s

This is the very agency that has the knowledge and ability to craft reasonable hobby rules that would ensure the multitude of new drone owners know and abide by safety regulations. Instead it emboldened Congress to start crafting drone rules via legislation that have the very real possibility of crippling this industry (i.e. Feinstein’s Drone Federalism Act). Congress doesn’t have the knowledge base to craft such legislation, and can only produce knee jerk regulations in order to appease their constituents. Giving that ability back to the FAA, and keeping an eye on the rule-making process, is the best way ensure hobbyists understand the consequences of reckless flight. Crafting reasonable hobby regulations, educating new drone owners about those rules, and then enforcing them when necessary, is the most effective way to ensure the safety of the NAS. And who is better equipped to do that than those people?

Between the lack of waivers and the lack of movement in figuring out a system to handle waivers, the FAA has found themselves largely behind the 8-ball. So much so that they could have put themselves in a positioned themselves in dangerous territory.

Overall, it’s refreshing to see the FAA recognizing its missteps and asking for help. It’s easy to be concerned about who seems to have the most influence in offering that help. It seems to me that this process may end up producing a pay to play system, and pushing the small operator too far out in the margins to create a viable business plan.

The big players have some great ideas, and the money and legislative muscle to move this industry forward. But the vast majority of this industry is comprised of small operators and companies. And we have some pretty good ideas too.

How about adding a small market panel to next year’s symposium? Making it more affordable for one or two person outfits would be a nice option as well.. Better yet, maybe even a working panel of small operators? After all, we are the vast majority of the drones in the sky, and most definitely the ones that are in the public eye the most. Part of the process is public perception of drones. And who would be better at educating the public than those of us flying in front of the public’s eye?

Listen to the little guys too, keep making progress and let’s progress this industry as a team!

–Paul

Check Out our podcast for further details on the conference. Http://askdroneU.com

Listen to it on iTunes:

Add Your Comment